How come, in the Bible, the Lord not only calls himself jealous, but acts like it’s a good thing? For just one of many examples:

“Thou shalt worship no other god: for the LORD, whose name is Jealous, is a jealous God”

Exodus 34.14 KJV.

This may be strange to read. Isn’t jealousy a manifestation of envy and spite? Why would a benevolent God call himself jealous? Who would an omnipotent God even be jealous of to begin with? The British atheist writer Richard Dawkins, in his book The God Delusion (2006), gave a well-known list of accusations: “The God of the Old Testament is arguably the most unpleasant character in all fiction: jealous and proud of it; a petty, unjust, unforgiving control-freak…” (p. 31 [Archive.org]) et cetera. Notice how “jealous and proud of it” is on the top of the list.

What’s up with this? How come the Bible attributes to God, who scripture calls benevolent, a trait that is generally considered to be unpleasant?

Jealousy versus envy

In modern English “jealousy” is usually used as a synonym for “envy.” But there is actually a difference between the two. Merriam-Webster Dictionary has a Usage Notes section on “Jealous vs. Envious.” In short, while the two concepts sometimes overlap, jealousy refers to worrying that someone might take what’s yours, while envy is wanting what belongs to someone else.

It’s not just the dictionary but also psychologists who say there is a difference between the two. In the magazine Psychology Today, there’s an article written by Richard H. Smith entitled “What Is the Difference Between Envy and Jealousy?” (3 Jan. 2014). He cites a paper titled “Distinguishing the experiences of envy and jealousy” published in 1993 to underscore his point. Psychologists almost all agree that jealousy and envy are two different emotions, and although they often overlap, they are not interchangeable.

So in short, jealousy is guarding what is yours (and is often about people), while envy is wanting what is someone else’s (and is often about objects). This difference is not only known to modern scholars and scientists, but was known to the ancients too as we will see.

What jealousy refers to

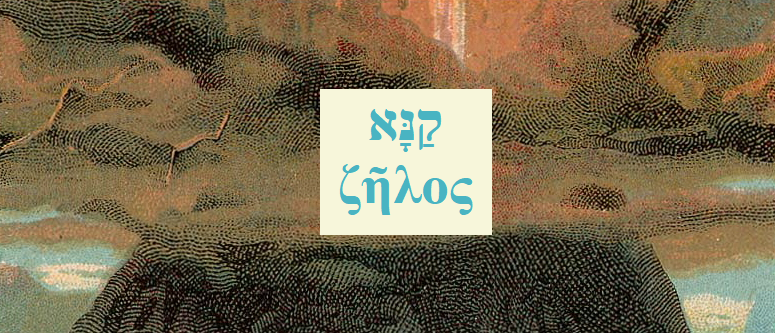

The word “jealous” is one of the many words in English that we borrowed from Greek; it comes from ζῆλος (zêlos). If that word sounds like “zealous” to you, that’s because the words “jealous” and “zealous” share this same origin. The Latin-speaking Romans borrowed the Greek word; the Latin word for “jealous” was zēlōsus, and “jealousy” was zēlus.

So to the ancient Greeks, jealousy was zeal. It meant to burn with a passion, to be willing to fight for something. It could be a zeal for self-improvement, a zeal for possessions, a love of something, a hate of something, et cetera. It could be used in a positive way (e.g. Demosthenes saying “They were tokens of emulation (ζῆλον) and honorable ambition“, Against Timocrates §181), or in a negative way (e.g. Hesiod mentioning “Envy (ζῆλος), foul-mouthed, delighting in evil“, Works & Days §195) as zeal is not inherently good or bad. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle spoke highly zeal/jealousy — which is translated as “emulation” in the below text — and actually contrasts it with envy:

Let us assume that emulation (ζῆλος) is a feeling of pain at the evident presence of highly valued goods, which are possible for us to obtain, in the possession of those who naturally resemble us – pain not due to the fact that another possesses them, but to the fact that we ourselves do not. Emulation (ζῆλος) therefore is virtuous and characteristic of virtuous men, whereas envy (φθονεῖν) is base and characteristic of base men; for the one, owing to emulation, fits himself to obtain such goods, while the object of the other, owing to envy, is to prevent his neighbor possessing them.

Aristotle, Rhetoric 2.11, translated by J. H. Freese. Underlining and Greek words added by me.

We can see this in the New Testament. Look at how ζῆλος is used in the letters of Saint Paul you will see that it is used in both a negative way way (e.g. “the works of the flesh are manifest … hatred, variance, emulations [ζῆλοι], wrath,” Galatians 5.19-20) or in a positive way (e.g. “I am jealous over you with godly jealousy [ζήλῳ],” II Corinthians 11.2) — again, much like with other ancient Greek texts, this is because it is talking about zeal whether good or bad. While sometimes ζῆλος is talking about envy, ancient Greek had it’s own word for envy specifically; φθόνος (phthónos), which also refered to ill will in general, and in the New Testament always refers to envy. This is translated into Latin as “invidius,” which is where the English word “envy” comes from.

Here is an interesting note on how “zelus” was used in Latin: St. Augustine of Hippo, in his Confessions, described God with a series of contrasts like “always working, yet ever at rest; gathering, yet needing nothing” (Conf. 1.4 [NPNF 1/1:46]) et cetera. When he gets to God’s jealousy in the same part, he says God is “jealous, yet free from care” (“zelas, et securus es” [PL 32:663] in Latin). Note that Augustine contrasts “jealous” (“zelas“) with being carefree and secure (“securus“), rather than contrasting it with love or kindness.

Hebrew is one of the languages that didn’t make a distinction for much of history. Before vowel markers were used in the language, קנא (K-N-A) was used for both jealousy and envy. However the Masoretic Text introduced vowel markers to the Hebrew Bible in the early middle ages. The Masoretic vowel markers made a distinction between קַנָּא (qannā’) and קָנָא (qānā’), with the former meaning “jealous” and the latter meaning “envious.” Keep in mind that Ancient Hebrew wasn’t as complex as other languages, and similar concepts often didn’t get distinctions until later. The Masoretic rabbis thought there was enough difference between jealousy and envy that they, like the Greeks, should have different words for them.

God the husband

If you read the Bible you will notice that God never is described as being “jealous of” anyone. Rather he is always described as being “jealous for” people and things. There’s a difference. He says “I am jealous for Jerusalem and for Zion with a great jealousy” (Zecheriah 1.14 KJV), and “I bring again the captivity of Jacob, and have mercy upon the whole house of Israel, and will be jealous for my holy name” (Ezekiel 39.25 KJV). If you swapped out “jealous” for “envious” in these verses they would make no sense, but if you swapped out “jealous” for “zealous” they would work just fine. The jealousy of God is clearly not a spiteful envy (how can you be envious of your own name?), but rather a zealous guarding of what belongs to him.

But what is he guarding? Paul wrote to the Church of Corinth saying “I am jealous over you with godly jealousy: for I have espoused you to one husband, that I may present you as a chaste virgin to Christ” (II Corinthians 11.2 KJV). The Church as an institution is personified as the Bride of Christ, and the Church is “married” to him in the sense that the Church serves no other God as a wife is married to no other husband. Jealousy, in the context of God, means fidelity, honestly, loyalty, and commitment. “For this cause shall a man leave his father and mother, and shall be joined unto his wife, and they two shall be one flesh. This is a great mystery: but I speak concerning Christ and the church” (Ephesians 5:31-32 KJV).

If the Church serving God is marriage, then what would worshiping false gods be? It would be adultery. One of the most common analogies used in the Old Testament is comparing idolatry (serving false gods) with adultery. If you ever wondered why the Mosaic Law calls idolatry “whoring after their gods” (Exodus 34.15-16), now you know why. Eventually the Israelites did “go a whoring” after false gods. Through the prophet St. Ezekiel, the Lord gave a warning to the fallen nation in the form of an analogy:

On the day you were born your cord was not cut, nor were you washed with water to cleanse you, nor rubbed with salt, nor wrapped in swaddling cloths. No eye pitied you, to do any of these things to you out of compassion for you, but you were cast out on the open field, for you were abhorred, on the day that you were born. And when I passed by you and saw you wallowing in your blood, I said to you in your blood, ‘Live!’ I said to you in your blood, ‘Live!’ I made you flourish like a plant of the field. And you grew up and became tall and arrived at full adornment. Your breasts were formed, and your hair had grown; yet you were naked and bare.

When I passed by you again and saw you, behold, you were at the age for love, and I spread the corner of my garment over you and covered your nakedness; I made my vow to you and entered into a covenant with you, declares the Lord GOD, and you became mine. Then I bathed you with water and washed off your blood from you and anointed you with oil. I clothed you also with embroidered cloth and shod you with fine leather. I wrapped you in fine linen and covered you with silk. And I adorned you with ornaments and put bracelets on your wrists and a chain on your neck. And I put a ring on your nose and earrings in your ears and a beautiful crown on your head. Thus you were adorned with gold and silver, and your clothing was of fine linen and silk and embroidered cloth. You ate fine flour and honey and oil. You grew exceedingly beautiful and advanced to royalty. And your renown went forth among the nations because of your beauty, for it was perfect through the splendor that I had bestowed on you, declares the Lord GOD.

But you trusted in your beauty and played the whore because of your renown and lavished your whorings on any passerby; your beauty became his. You took some of your garments and made for yourself colorful shrines, and on them played the whore. The like has never been, nor ever shall be. You also took your beautiful jewels of my gold and of my silver, which I had given you, and made for yourself images of men, and with them played the whore. And you took your embroidered garments to cover them, and set my oil and my incense before them. Also my bread that I gave you — I fed you with fine flour and oil and honey — you set before them for a pleasing aroma; and so it was, declares the Lord GOD. And you took your sons and your daughters, whom you had borne to me, and these you sacrificed to them to be devoured. Were your whorings so small a matter that you slaughtered my children and delivered them up as an offering by fire to them? And in all your abominations and your whorings you did not remember the days of your youth, when you were naked and bare, wallowing in your blood.

Ezekiel 16.4-22 (ESV). Underlining by me.

The passage goes on and gets more graphic, but hopefully you get the point. Jerusalem, in abandoning the Lord, was like a cheating wife. The false gods and other nations were like paramours. That’s why the Lord describes her killing her children for them; ritual child sacrifice was what the false idols of the time demanded. Every reason that a husband has to be protective of his literal wife, is magnified ten thousand times when it comes to the Lord being zealous for his spiritual wife the Church.

A caveat

Now, even with everything I just said, I should note that zeal/jealousy itself isn’t noble in and of itself. There are different forms of zeal/jealousy, hence is why St. Paul clarified that he had a “godly jealousy” (II Corinthians 11.2). The ungodly kind arises out of being selfish and possessive, looking out primarily for your own pride. Pathological or delusional jealousy can wreck a relationship, and being patholigically obsessed with the idea that your spouse is cheating on you is obviously unhealthy.

The godly kind, however, arises out of love for the one you want to protect. In one of his homilies, St. John Chrysostom discussed the difference between the “godly jealousy” St. Paul describes, and the ungodly jealousy many people are familiar with:

“For I am jealous over you,” saith Paul, “with a godly jealousy, for I espoused you to one husband that I might present you as a pure virgin to Christ.” What wisdom and understanding! “I am jealous over you with a godly jealousy.” What means this? “I am jealous,” he says: art thou jealous seeing thou art a spiritual man? I am jealous he says as God is. And hath God jealousy? yea the jealousy [ζηλοῖ] not of passion, but of love, and earnest zeal [ζηλοτυπίᾳ]. I am jealous over you with the jealousy of God. Shall I tell thee how He manifests His jealousy? He saw the world corrupted by devils, and He delivered His own Son to save it. For words spoken in reference to God have not the same force as when spoken in reference to ourselves: for instance we say God is jealous, God is wroth, God repents, God hates. These words are human, but they have a meaning which becomes the nature of God. How is God jealous? “I am jealous over you with the jealousy of God.” Is God wroth? “O Lord reproach me not in thine indignation.” Doth God slumber? “Awake, wherefore sleepest thou, O Lord?” Doth God repent? “I repent that I have made man.” Doth God hate? “My soul hateth your feasts and your new moons.” Well do not consider the poverty of the expressions: but grasp their divine meaning.

John Chrysostom. Homilies on Eutropius, II.7 (NPNF 1/9:256). (Greek text inserted by myself by consulting PG 52:402.)

Since “God is love” (I John 4.16 KJV), he is naturally protective of those he loves. He is not envious, for there is nobody for him to be envious of, but he is rightfully protective of his heavenly bride. As mentioned before, God is “jealous for” his people, but is never “jealous of” anybody. That is an important distinction.